The Main Rationalists

The term ‘rationalism’ is from the Latin ratio, meaning

reason. Rationalism asserts that knowledge can be only attained through pure thinking or reasoning

alone. Also known as a priori (prior to

experience) knowledge – that some ideas are truly independent of experience.

There is another philosophical category known as Idealists. Bridging the two schools the following philosophers falls

into the Rationalist-Idealist camp: Socrates, Plato, Berkeley, Hume,

and Kant. Berkeley and Hume are classified as ‘Empiricists’ philosophers

which make their own philosophy very unique which validates the claim that philosophers are not always easily

categorized; that their philosophies are stubborn to straightforward, brief explanation – the intent of

this web-site.

The key distinction of the idealist is that they deny the independent existence of

matter. That mind is primary and matter is secondary. The idea that matter is mind

dependent is core to the “Mind over Matter” versus “Matter over Mind” debate. Additionally, the

Rationalist-idealist contend that Beauty, Truth and Goodness (morality)

are primary qualities of their philosophy.

Socrates (ca 470–399B.C.E.)

Socrates is considered the founder of Western

Philosophy. The

body of his key ideas and principles, since he taught by oral presentation and produced no written works, has

been largely deciphered by his most prominent students, Plato and Xenophon,

in addition to the legions of historians and philosophers who have written on him since.

Sophists

A prerequisite for status in Athenian culture (5th-century B.C.) was to speak

well. Traveling teachers known a ‘Sophists’ or “men who

make you wise” taught argument and rhetoric in addition to “how to do well in

life”. Sophistry was in essence political philosophy and was midwife to philosophy’s

becoming. Sophistry’s dark side: cunning,

sometimes manifested as trickery.

Plato’s

Dialogues

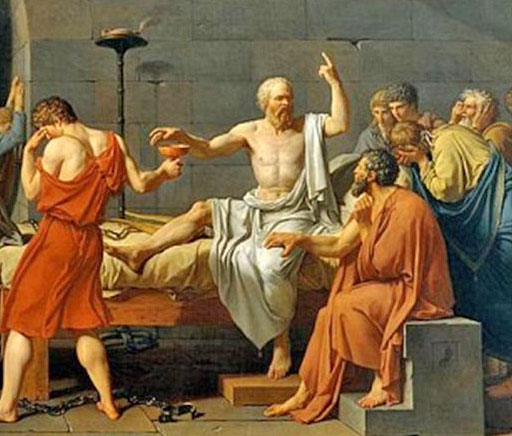

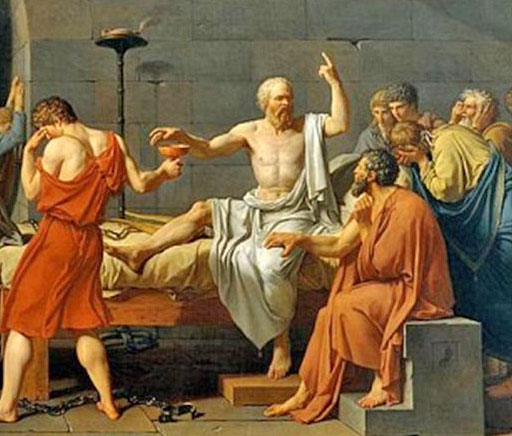

Portrayed as the protagonist Socrates is best known through Plato’s dialogues where

thought and insight on moral and philosophical problems are brought to light by the Socratic method of questioning

and discourse. Socrates inquisitive approach positioned him as a moral and social critic of Athenian

leadership, which ultimately led to his trial and execution for corrupting the minds of young Athenians.

Socrates brand of sophistry was that he did not charge for his teaching. Rather than

helping his students to prevail in their opinions, he trained them to develop a method of argument that would

elicit the truth and virtues. For Socrates charity and zeal to teach well, Plato and others christened him not just

as one among many wise men but specifically as a philosopher – literally translated as "lover of

wisdom".

Reason Reigns Over

Emotion

Socrates firmly believed that before humans can understand the world, they first need

to understand themselves – the only way to accomplish that is with rational thought. In his dialogue ‘Phaedrus’

Plato uses the Chariot

Allegory to explain Socrates’ view of the human soul where Man is composed of two parts: a

body and a soul. The soul itself has two principal parts: an Irrational part, which is the emotions and desires;

and a Rational part, which is our true self. In our everyday experience, the irrational soul is drawn into the

physical body by its desires and merged with it, so that our perception of the world is limited to that

delivered by the physical senses. The rational soul is beyond our awareness, but sometimes communicates via

images, dreams, and other means.

Immortal Soul

Socrates believed that souls are

immortal. He argued that Athenians were wrong-headed in their emphasis on families, careers, and politics at the

expense of the welfare of their souls. The common maxim of the times – “I know that I know nothing” – signified

Athenian ignorance, non-virtuous behavior and a lack of concern of the consequences of

misdeeds.

Socrates believed that humans know all things in a disembodied

state and learning in the embodied state is a process of recollection in action. Similar to

the philosophical doctrine knowns as ‘innatism’ – that the mind is born with ideas or knowledge and that the mind

is not a blank slate (“tabula rasa”) at birth. Socrates demonstrated ‘recollection in action’ by posing a

mathematical puzzle to an uneducated servant. The servant is ignorant of geometry, however by Socrates’

questioning and clever drawing of geometric

figures the servant was able to deduce how the area of a square relates to Pythagorean

right-angled triangles.

René Descartes (1596–1650)

"Dubito ergo cogito, cogito ergo

sum" (I doubt therefore I think, I think therefore I

am)

‘First Modern

Philosopher’

Descartes, known as the 'first modern philosopher', laid the foundation for 17th-century

continental rationalism, later advocated by Spinoza and Leibniz, and was later opposed by the empiricist school of thought

consisting of Hobbes, Locke,

Berkeley and Hume. Descartes has been described as a ‘Conceptualists’, a ‘Rationalist’ and a ‘Dualist’ (not ‘nominalist’), Modern philosophy and

modern epistemology effectively begins with Descartes.

Descartes claim that all we are directly aware

of is the content of our own conscience – a problem that modern philosophy has been wrestling with ever

since.

Descartes’ Key Works include 'Meditations on First Philosophy, in which the existence of God and the immortality of the soul are

demonstrated' (1641), ‘Principles of Philosophy’ (1644) and ‘The Passions of the Soul and Other Late

Philosophical Writings’ (1649). ‘Meditations’ influenced the works of Spinoza.

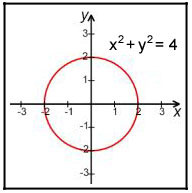

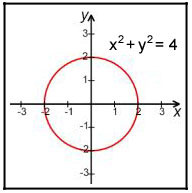

Cartesian Coordinate System

(CCS)

Descartes invention of Cartesian coordinates revolutionized mathematics by providing a link between Euclidean

geometry and algebra – geometrical problems were able to be solved using algebraic equations.

Meditations on First

Philosophy

‘Meditations of First Philosophy’ is made up of six meditations. Descartes attempts to discards all belief in

things that are not absolutely certain and then tries to establish what can be known for sure. Descartes

thesis is a logical one (ie, Descartes proves God and then says 'since God is good'), not a historical thesis (eg,

'confidence in science arose because of...').

1) I doubt. Descartes stance is profound skepticism where the necessary precondition for

skepticism as a foundation for scientific inquiry is thought. Descartes introduces a new method of radical

skepticism: methodic doubt, where truths are gained "without any sensory experience". Truths that are attained by

reason are broken down into elements that intuition can grasp,

which, through a purely deductive process, will result in clear truths about reality.

The epistemology of methodic doubt led Descartes to claim that reason alone determines knowledge and that it could

be done independently of the senses. For instance, his famous dictum, cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”),

is a conclusion reached a priori and not

through an inference from experience. Descartes posited a metaphysical dualism, distinguishing between the

substances of the human body ("res extensa") and the mind or soul ("res cogitans"). This crucial distinction

would be left unresolved and lead to what is known as the mind-body

problem, since the two substances in the Cartesian system are independent of each other and

irreducible. As the late philosophy professor Daniel

Robinson quips, “The modern age is with us – warts and all”.

2) I exist, I am a thinking thing. Not just 'cold' calculation. Includes conscience feelings, acts

of the will (affirming and denying), Intellect is not separate from emotion. To say "I think therefore I exist" is

similar in saying "I'm conscience therefore I exist".

3) God exists. The crucial a prior question: the idea of God.

4) Reliability of reason & problem of error.

5) Necessary Truth regarding material bodies.

6) Contingent truths about material existence.

Critiques

1) David Hume’s ‘An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding’:

Descartes’s ambition exceeded his reach,

and although his though he remained influential for many years, especially in his native France, its practical

value never matched its theoretical elegance. The supposed deduction of precise laws of motion from the pure

geometry of extension proved elusive, and Cartesian mechanics was unable to yield convincing predictions either of

terrestrial dynamics (e.g. flying projectiles and colliding billiard balls), or the celestial orbits of the

planets. Indeed, the careful observations and calculations of Tycho Brahe and Johannes

Kepler had revealed these orbits to be elliptical rather than circular, and this gave

particular difficulties for the Cartesian vortex theory. Its death knell came in 1687, when Isaac

Newton was able in his Principia Mathematica to prove results indicating the impossibility of

a vortex yielding elliptical motion.

2) The Realists

The realists who argue that we have direct

awareness of reality rejects Descartes method. Philosophy professor Dr. Holmes comments,

“The fact that you are cold proves you have a body! Ever been seasick? I can imagine anybody who is

seasick and still has a week at sea to go and even imagining they don't have a body.”

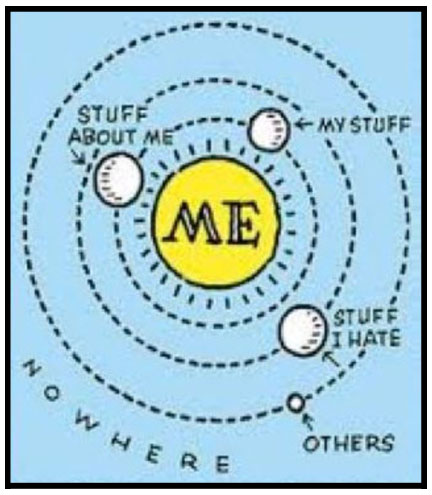

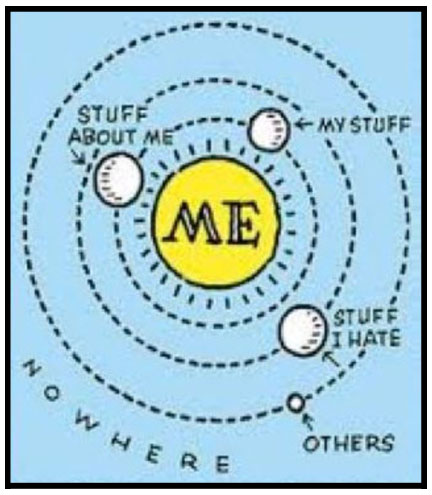

3) Descartes Solipsistic

Demon

Descartes and any theory of knowledge that adopts the Cartesian egocentric approach as its basic frame of reference

is inherently solipsistic. Solipsism is a view that nobody takes seriously in the sense of holding it. It's sort of

a dead-end street. Literally a solipsist is one who says, "I and only I exist".

Three problems of solipsism of the present moment:

1) All I know is that I exist

2) Discontinuity of my own consciousness.

3) The problem of memory. Memory being the present representation of a past consciousness.

How do we know whether the past consciousness is in one’s mind? Only by memory. What is memory? Memory is present

consciousness not a past consciousness. You cannot have a direct awareness of a past consciousness. Because

you're not in the past, you're in the present. So all we know is our present consciousness.

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677)

Spinoza was raised in the Portuguese-Jewish community in

Amsterdam. In his magnum opus, 'Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order'

(1677), Spinoza's applied the methods of Euclid to

philosophy using foundational definitions and axioms to define propositions and corollaries (eg, "The human Mind

cannot be absolutely destroyed with the Body, but something of it remains which is eternal."). In essence

He was trying to provide a scientific basis for universal

truth.

Top thinkers were uneasy in regards to ‘Ethics’ unresolved

obscurities and the “forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid's geometry”. Even Goethe admitted

that he "could not really understand what Spinoza was on about most of the time." Some consider Spinoza to be

a rationalist, some saw him as a kind of mystic, while others viewed him as a pantheist rather than a

theist.

Due to his controversial ideas regarding the authenticity of the

Hebrew Bible and the nature of the Divine Spinoza and his family were expelled from Jewish society. His

books were later added to the Catholic Church's Index of Banned Books. European philosophers who read

Spinoza did so in secret. Locke,

Hume,

Leibniz and Kant

all stand accused by later scholars of indulging in periods of closeted Spinozism.

Although heavily influenced by Descartes, Spinoza opposed his philosophy of mind-body

dualism; his ideas earned Spinoza recognition as one of Western philosophy's most important

thinkers. Hegel comments, “Spinoza

wrote the last indisputable Latin masterpiece, and one in which the refined conceptions of medieval philosophy

are finally turned against themselves and destroyed entirely…You are either a Spinozist or not a philosopher at

all."

The 19th-century Romantics very

appreciated the works of Spinoza (Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

Johann von Goethe,

Matthew Arnold).

God & Nature

Philosophy professor Dr. Arthur Holmes comments on the nature and views of the ‘mystic’

philosopher: “Spinoza is a ‘metaphysical monist’ or double aspect monism which includes the infinite and

the finite; the material and the logos (call it nature or God). We haven't met a metaphysical monist

because of the Judeo-Christian influence…The Stoic ethic and metaphysic exists in Spinoza; he’s very

systematic. Stoic metaphysic implies nature pantheism where nature is divine. God and nature are one

and the same thing (F-7) –

nature as providence.…Mind is not a substance that is separate from a body; body is not a substance separate

from mind. Mind and bodies are not substances separate from God. Man is the finite modes of the being of

God. In that sense we do think God's thoughts after him”.

Spinoza’s 'finite modes' are similar to New

Thought's 'divine

within’ – an intellectual love of

God.

Conatus

The Conatus ('striving') principle is associated with God's will in a pantheist view of Nature and the

instinctive "will to live" of living organisms. It can be described as inner push, inner pull or an inner drive. It

runs throughout everything. The very nature being. Besides Spinoza, other philosophers who have made contributions

to the principle of Conatus include Descartes, Leibniz and Hobbes.

Professor Holmes continues, “It’s as if Spinoza is saying, "now

wait a minute you mechanistic science. Is matter that

dead? Or really is it a bundle of energy?" If that's the sort of thing that's underlying

this then Spinoza is jumping a couple of hundred of years ahead of his time. Is matter dead, inert, acted only

from outside? Which is a mechanistic science view. Or perhaps the pre-Socratics, who weren’t crazy after

all, who said that 'matter is some sense alive, full of divinity'.

Free Will &

Determinism

For Spinoza true freedom was not caprice to do as thou wilt, but instead recognition of the laws of nature. Human

society was a part of nature, and thus bound to the deterministic laws of nature.

By exploring human nature, one could understand one’s own true nature and thus achieve true freedom. For Spinoza

a deterministic universe is nothing to despair over, instead it is a source of joy because it means that no

event is ever to be regretted. To love life and all its happenings, all its fortunes and misfortunes is to

love God.

The source of optimism in Spinoza’s philosophy is the understanding that through comprehending the deterministic

nature of the universe, one could adjust one’s emotional state to express joy in all that is the

case.

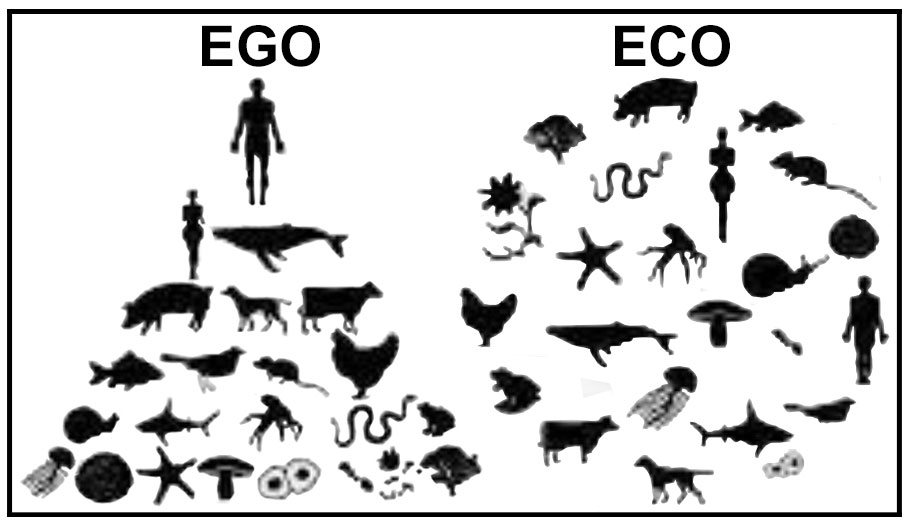

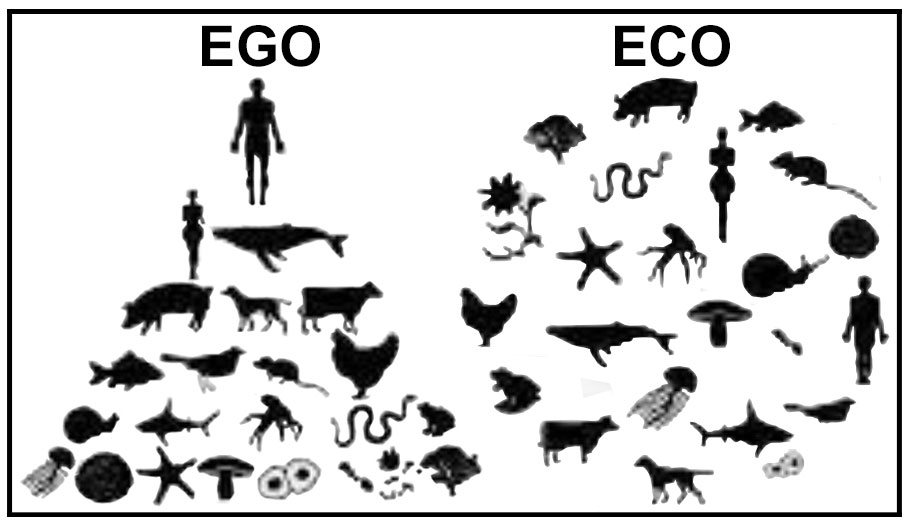

‘Ego' versus ‘Eco’

Integral philosopher Ken Wilber in his

‘Theory of Everything’ (2000) comments: “The Enlightenment philosophers (“Ego camps”) denied Spirit, whereas the

Romantics (“Eco camps”) claimed nature is Spirit. The Romantics desired wholeness, harmony and union. Most of

the Romantic criticisms could be summarized as an extreme uneasiness with the Ego’s repressive tendencies. The

Enlightenment criticism of Eco is that they perpetuate regression (ie, ‘get back to nature’). To reconcile these

two positions — to transcend nature so as to find moral freedom and autonomy (Fichte) or become one with nature

so as to find unity and wholeness (Spinoza) — still the critical dilemma in today’s world…The Romantics wrongly

conclude that Culture is not on the way to the true Self; that it is simply a crime against the “true self” of

your biocentric feelings. They incorrectly recommend not to move forward to Fulcrum-7

(The Psychic) and the Eco-Noetic Self, but that we move back to Fulcrum-2 (Emotional Self) and the biocentric or

eco-centric or ecological self…The enlighten 'kosmic' understanding: Nature is objective Spirit,

mind is subjective Spirit.”

Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716)

"Reality cannot be

found except in One single source, because of the interconnection of all things with one another" —

Gottfried Leibniz

Leibniz, a polymath, studied philosophy, science and

mathematics. His significant contribution in mathematics was the development of differential and

integral calculus (independent

of Isaac Newton). Besides a being a proponent of rationalism, in general, Leibniz’s philosophical school

is in the realm of idealism.

Monads – A

Pathway in Resolving the Science-Religion Conflict

Akin to Bishop

Berkeley Leibniz saw conflicts emerging between the new discoveries of 17th century

mechanistic science and Christian religion. Materialism was on the rise: the philosophy of Deism was built upon the

foundation of Newtonian

physics where nature operates according to its own fixed mechanical laws.

To work out the Science-Religion conflict Leibniz sidestepped Spinoza's naturalistic

pantheistic interpretation of mechanistic science, which he didn’t like, and even avoided the Deistic picture of

God that evolved from the Newtonian discoveries by proposing a metaphysical

alternative understanding that the ultimate constituents of reality consists of 'Monads'.

The Problem of Evil

In his work ‘Theodicy: Essays on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of

Evil’ (1710) Leibniz introduces the term theodicy which attempts

to answer why a ‘good’ God permits the manifestation evil and for the suffering and injustice that exists in the

world. His controversial conclusion, that our world is the best possible world that God could have created, was

ridicule by his contemporaries such as Pierre Bayle and even lampooned by Voltaire in his satirical novella

‘Candide’ (‘Panglossianism’, in reference to Dr. Pangloss – meaning ‘all

talk’ – was the derogatory vocabulary of the day). Leibniz response to his distractors is that it can be

proved that God is an infinitely

perfect being, and that such a being must have created a world that has the greatest possible balance of good

over evil.

Contemporary idealist metaphysical ‘religions’ or ‘societies’

solve the problem of ‘evil’ with a higher understanding of ‘Divine Power’. The upshot is that is a dark

planet for entities to learn to be positive in a

negative world. Negativity abounds in the world. Did God create it? No. Man alone is

responsible for it. Through free will choice, some people invert good to make a negative. We all have free

choice of a path of Light or Darkness. The principle is almost like electricity: a rise in light or goodness is

matched a rise in darkness or evil. What is evil? Basically greed (if it’s not god-centered). At the heart

of every evil is greed (important to not confuse having abundance with greed; an abundance ‘for the greater

good’). God is pure and constant in Their

love. People are erratic and subject to petty behavior. Never ascribe to God such pettiness,

for that makes God imperfect – that is not in Their nature.

Metaphysical publications on evil: Journey of the

Soul' series; ‘The Art of Being

Yourself’.

Bridge to

Religion

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804)

"The evil that men do lives after

them; The good is oft interred with their bones" – Julius Caesar (3-2), William

Shakespeare

Immanuel Kant continues to be considered among

the most essential figures in modern philosophy - an advocate of reason as the source for morality and a thinker

whose ideas continue to permeate ethical, epistemological, and political debate.

Kant’s philosophical ‘big ideas’ include:

critiques of Reason &

Judgment; Categorical

Imperative; concepts of time & space and cause & effect; the synthesis of the

philosophical schools of Empiricism &

Rationalism to the idea that the principle of morality is freedom. If

you’re living in a democratic society that protects individual

freedoms, you have Kant partially to thank for that.

The root of these exceptional ideas is the free play of ideas where the exceptional

person sees things behind the world of mere appearances and gives us clarifying insights on what use to be

mysteries, tyrannies or other oppressions.

Kant is

Integral

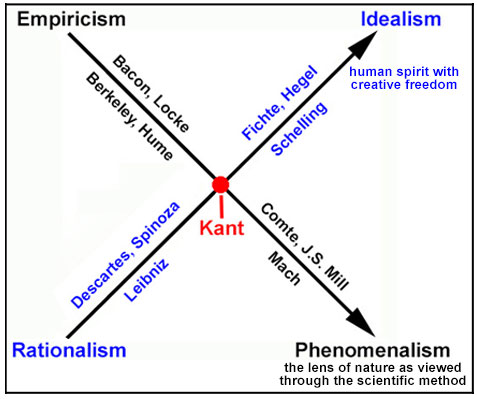

Kant calls for combining rationalism (reason) and empiricism (empirical evidence),

for all philosophies from natural philosophy (science) to metaphysics

(extra-scientific philosophy). In all truth claims, we need both the empirical and the rational outlooks to

understand the world and ourselves – the ‘integral’

Kantian position.

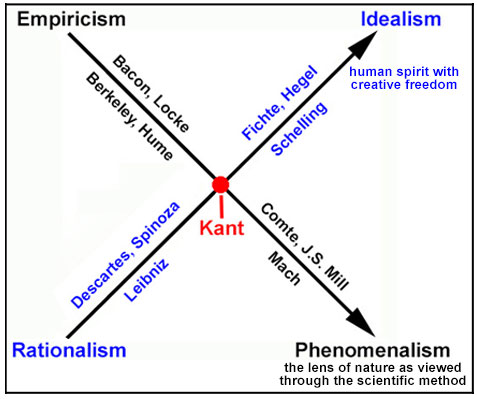

The visual diagram below illustrates the trajectories of philosophical traditions

from the 17th-century to the 19th-century and Kant’s place in it.

The Empirical tradition of English-speaking

philosophers (Bacon,

Locke,

Berkeley, Hume)

grew into what is called ‘phenomenology’ –

largely represented in the writings of Auguste Comte, John Stuart Mill and Ernest

Mach. Phenomenology’s theme: scientific

criteria or the scientific method should be used in judging human knowledge.

The Rationalist tradition of the European

continental philosophers (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz) or "Continental Rationalism” grew into what is called ‘idealism’, ‘metaphysical idealism’ or later ‘German Idealism’ (Johann

Fichte, Friedrich

Schelling, Georg Hegel).

Idealism’s theme: look at reality through the lens of human self-awareness or of the human spirit with creative

freedom.

Kantian Transcendental

Idealism

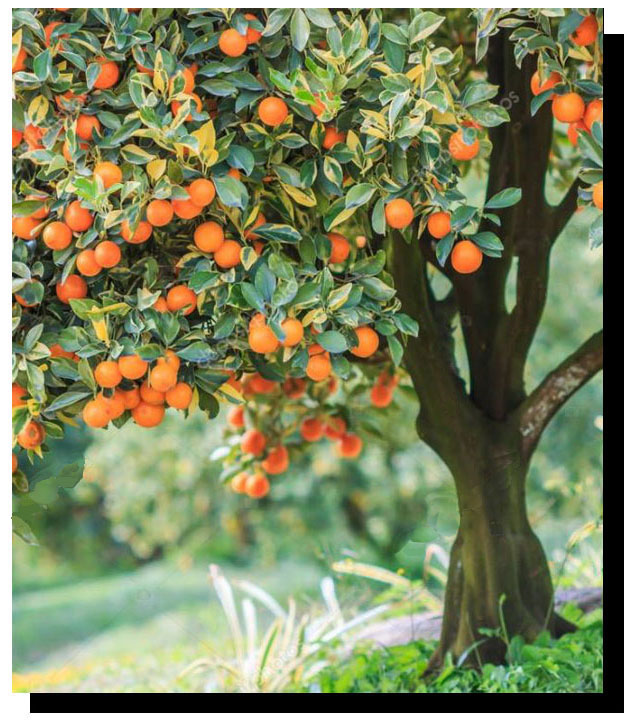

From the ‘tree’ called ‘The Critique of Pure

Reason’ (CPR) its ‘fruit’ became known as ‘Transcendental Idealism’ – a unique branch of

epistemology developed by Kant where both reason and experience are necessary for human knowledge. Kant’s term

‘transcendental’ signifies that certain knowledge transcends sensory evidence namely space and time which are

subjective forms of our sensibility ("Transcendental Aesthetic", CPR). Kant held that the world of appearances

(phenomena) is empirically real and transcendentally ideal. That we perceive phenomena through time, space and

the categories of the understanding. The 'seed' of Kant's transcendental idea, in the quest for knowledge, is to

access the inner resources of the human spirit, the inner resources of the human mind by a priori

reasoning. It is this notion that was taken to heart by Kant's philosophical successors.

Copernican

Revolution

The ‘Copernican Revolution’ is an analogy used

by Kant to illustrate the reversal of the subject-object relationship. Copernicus discovered that the earth revolves around the sun, while the

opposite was thought before him. In the ‘Critique of Pure Reason’ Kant reverses the traditional subject-object

relationship. Prior to Kant the object was central to the theory of knowledge, afterward the subject became

central to knowledge. In other words, Kant boldly suggested that the representation

makes the object possible rather than the object that makes the representation possible. That there

are experiences that could be acquired through ‘intuitions of the mind’ which introduces the idea that the human

mind is an active originator of experience rather than a passive recipient. That our mind is a creative,

intuitive and interpreting organism rather than a reactive and logical machine. It was an epic “Post-Modern

Watershed” moment in a pre-modern era.

The Influence of

Kant

● Shakespeare. "The

evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones” (Julius Caesar)

● Depth psychology (Jung, Freud); "Universal

Symbolism"

● Max Weber (on the cultural side)

● German Nationalism - collective identity

(19th-century nationalism)

● German Idealism (Hegel) - creative

ideas

● Romanticism

● Existentialism

● Post-Modern

Movement

There is a clever analogy that characterizes

the Analytic philosophical schools (US, UK) as being the House of Lancaster and the Continental philosophical

schools (France, Germany) as the House of York. Kant is King Edward III – the last common ancestor to those

houses. Continental philosopher Paul Ricoeur quips, "it is not exactly the same Kant", suggesting the

analytic/continental division can be represented as a struggle over Kantian legacy.

“What is

Enlightenment?” (Immanuel Kant, Berlinishcen Montasschrift, 1784)

#1 - “Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is

the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its

cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it without guidance from

another. Sapere Aude! [dare to know] ‘Have courage to use your own understanding!’ – that is the motto of

enlightenment.”

z

|