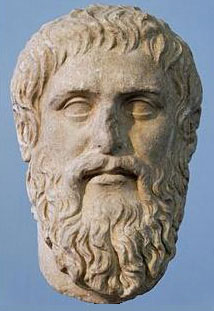

Plato “The price good men pay for indifference to public affairs is to be ruled by evil men.” — Plato

Plato (c. 428-347BC) was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science. Plato was a monist and posited that everything is made of a single substance. Socrates had created the philosophic life, but he was not a professional philosopher. The greatest pupil of Socrates was Plato, who left Athens in disgust after Socrates' execution in 399, but returned after 387, settled in a suburb called Academia. Plato established a private society of people known as the Muses, which later became source of the name ‘Museum’. One cannot underestimate the influence of Plato’s dialogues on Western philosophy. As Alfred North Whitehead put it: “The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.” The most important writings of Plato are his dialogues of which six stand out: Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Symposium and The Republic. The dialogues of Apology, Crito and Phaedo center on the death of Socrates. Ideas discussed within these three works are genuine knowledge as a form of recollection; the existence of ideal Forms or Ideas; the immortality of the soul; and metempsychosis (the passing of the soul after death into another body). Symposium discusses the metaphysics of love and attempts to connect man’s feeling for beauty with Plato’s theory of Ideas. Phaedrus, companion to Symposium, is also concerned with the nature of love. In Phaedrus Socrates teaches him through the use of myth – the analogy of the soul to a charioteer and a pair of winged horses, one noble and the other ignoble. Socrates expounds the idea of the soul’s immortality, its composite nature, and the realm of true knowledge, beauty, wisdom and goodness, toward which man’s noble nature aspires. The Republic contemplates the elements of the ideal state, the concept of justice, Plato’s theory of Ideas and the philosopher’s role in society. To explore the latter Plato invents The Allegory of the Cave to illustrate his notion that ordinary are like prisoners in a cave, observing only the shadows of things, while philosophers are those who venture outside the cave and see things as they really are. Plato’s metaphor shows the eternal conflict between the world of the senses (the cave) and the world of Ideas (the world outside the cave), and the philosopher’s role as mediator between the two. For Plato philosophy was not mere talk or introspection; it is the suspension of customary beliefs and opinions and the questioning of prevailing "truths". Using the myth of the 'golden cord' of Ariadne that allowed Theseus to retrace his steps out of the labyrinth after killing the Minotaur, criticism, questioning and reasoning is the 'golden cord' which Plato urged us to never let go of: lose it and we are pulled like puppets or slaves. Plato’s perfection of Socrates' Question and Answer (Q&A) technique led toward the discovery of formal logic and the rationalistic criticism of common beliefs (important in Hellenistic thought and in Christian polemics against paganism). Plato gives the earliest surviving account of a “natural theology” (circa 360 BC) in his dialogue Timaeus in where he present two worlds: the physical and eternal. The physical world changes and perishes and, thus, is the ‘object of opinion and unreasoned sensation’. The eternal world never changes which can be apprehended by reason. Plato’s two worlds is also expressed in the dualism of Material (physical) and Form (eternal). Material is always changing and therefore unknowable. Form can be known and must therefore be permanent.

Attempting to comprehend the ‘eternal’, Plato ponders a ‘pre-Genesis’ state: “Now the whole Heaven, or Cosmos, …we must first investigate concerning it that primary question which as to be investigated at the outset in every case – namely, whether it has existed always, having to beginning of generation, or whether it has come into existence, having begun from some beginning”. In his dialogue, Laws, we see Plato reflecting on the two grand movements in Religious/Philosophical matters - Ascend & Descend: “…which lead to faith in the gods? …One is our dogma about the soul…the other is our dogma concerning the ordering of the motion of the stars”. Carl Sagan said of Plato: "Science and mathematics were to be removed from the hands of the merchants and the artisans. This tendency found its most effective advocate in a follower of Pythagoras named Plato. He (Plato) believed that ideas were far more real than the natural world. He advised the astronomers not to waste their time observing the stars and planets. It was better, he believed, just to think about them. Plato expressed hostility to observation and experiment. He taught contempt for the real world and disdain for the practical application of scientific knowledge. Plato's followers succeeded in extinguishing the light of science and experiment that had been kindled by Democritus and the other Ionians." In the long run, Plato's influence would be overshadowed by that of his pupil Aristotle. Aristotle laid the bases for an answer by his studies of logic, his classification of the ways in which objects differ (the categories of knowledge).

z

|