Phenomenology

Phenomenology is an interpretative methodology that studies the structures of

consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The experience, along with

enabling conditions, is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the

object). Phenomenology is not a theory, not a system of thought nor a philosophical position. It is a

method.

Continental philosophers (Germany, France) have

carried on the interpretive aspects of philosophy whereas the dominate English-speaking philosophers (Britain,

North America) have typically shunned interpretative aspect and focused mostly on pragmatic and

empiric analytic studies. Another type of interpretative methodology is Hermeneutics which chiefly focuses on

the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts.

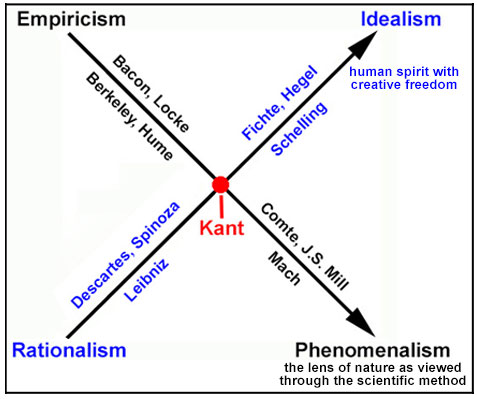

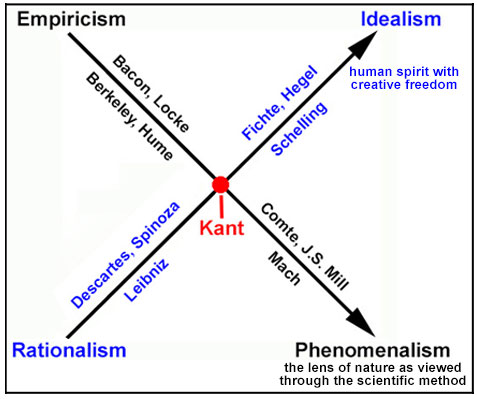

The visual diagram below illustrates the

trajectories of philosophical traditions from the 17th-century to the 19th-century (with importance of Immanuel

Kant).

The Empirical tradition of English-speaking

philosophers (Bacon,

Locke,

Berkeley, Hume)

grew into what is called phenomenology – largely represented in the writings of Auguste Comte, John Stuart Mill

and Ernest

Mach. Phenomenology is a reaction against mechanistic science which tells us about appearances

but not reality. It is a radical form of empiricism in that physical objects cannot justifiably be said to exist

in themselves – that physical objects are mind-dependent. Phenomenology as an ontological view of the nature of

existence can be traced back to Berkeley and his subjective idealism.

Phenomenology's general theme: scientific

criteria or the scientific method should be used in exploring, observing and judging

human knowledge. and human societal structures. The social scientist is not concerned about molecules,

atoms and electrons, but beings living, acting and thinking within a social structure.

Idealism general theme: look at reality through

the lens of human self-awareness or of the human spirit with creative

freedom. Phenomenology can also exist in 'Idealism' realm – testimony to the claim that

phenomenology is ‘more developed, more complex’ (see Transcendental Phenomenology).

Phenomenalism vs.

Phenomenology

Phenomenalism is not Phenomenology. An -ism is a position, a feeling, a belief.

Phenomenalism is ‘all we know are appearances'. An 'ology is the study of, a science of a subject. A methodological

thing. Phenomenology is the study of phenomena, but not saying that only phenomena can be

known.

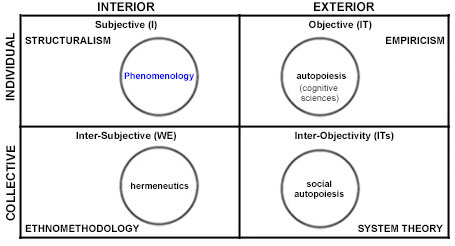

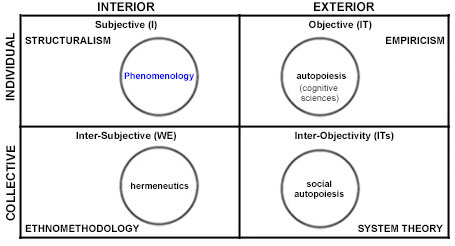

AQAL Map

Using Integral

Theory's AQAL map provides a visual tool to assist in understanding Phenomenalism. Since

Phenomenalism claims that that physical objects are reduced to mental objects, it exists in the

Individual-Subjective or Upper Left (UL) quadrant.

Over time phenomenology divided into several camps including

existential and transcendental phenomenalism.

Transcendental Phenomenology

(TPh)

Emmanuel Kant started transcendental philosophy; however it was Edmund Husserl

(1859-1938) who refined phenomenology as transcendental-idealist philosophy – similar in many ways to Kant’s

Transcendental

Idealism (the nuances of the differences is fertile ground for high academic debate and

reflection). Husserlian Transcendental Phenomenology is "the reflective study of the essence of

consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view." TPh takes the intuitive experience of

phenomena as its starting point and then to study experience without reference to assumptions posited by

experience. Husserl is considered to be the founder of transcendental phenomenology,

An interesting ‘clock & dagger’ story begins after the death of Husserl whose

students were alarmed with the Nazis intent to destroy his writings since he was Jewish. Before the Nazis arrived

Husserl’s manuscripts (approximately 40,000 pages) and his complete research library were smuggled to the Roman

Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium by the Franciscan priest Herman Van Breda. The university became home to

the Husserl-Archives of the Higher Institute of Philosophy and a major center for phenomenology

studies.

Transcendental phenomenologists: Edmund Husserl

(1859-1938), Amadeo Giorgi

Existential

Phenomenology

Philosophy must begin from experience but argues for the temporality of

personal existence as the framework for analysis of the human condition. Temporality as opposed to a higher

non-temporal state of

eternity, which is co-extensive with the infinite and eternal now of God (no time on ‘The

Other Side’). A "primordial" or "original" time that it is finite. It comes to an end in death. Existential

phenomenology differs from transcendental phenomenology by its rejection of the transcendental

ego.

Existential phenomenologists: Martin

Heidegger (1889–1976), Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995), Gabriel Marcel (1889–1973),

Jean-Paul Sartre

(1905–1980), Paul Ricoeur (1913–2005) and Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–1961).

Extreme

Phenomenalism

In the late 19th century, an extreme form of phenomenalism was formulated by Austrian

physicist Ernst Mach, later developed and refined by the Logical

Positivists. Mach rejected the existence of God and denied that

phenomena were data experienced by the mind or consciousness of subjects. He held the view that sensory

phenomena were "pure data" whose existence is anterior to any arbitrary distinction between mental and physical

categories of phenomena.

Anti-Phenomenalism

Recent academic research (2017) claims that phenomenalist interpretations of Kant are

out of fashion. The most common complaint from anti-phenomenalist critics is that a phenomenalist reading of Kant

would collapse Kantian idealism into Berkeleyan idealism.

Math and logic are problematic for they are independent of sensory verification (one answer is to

consider them conventions of language). Also, ethical (right &

wrong) and aesthetic (beauty) statements are

neither true nor false because they could not be verified (conflicts with the Verification Principle, a

philosophical doctrine fundamental to the school Logical Positivism).

Ironically, one criticism points out that the

verification principle itself is not - by its own criteria - meaningful. It is not an analytic truth (a 'convention

of language') and neither is there any possible or actual sense experience that could be said to verify

it.

Last Word

The various camps of phenomenology take various positions on whether we live in a

spiritual or mental universe. There are possible perceptions of objects

which are never perceived - although they are capable of being so. Can one have ‘ESNP’? – Extra Sensory

Non-Perception. How does the phenomenologist answer the koan problem in

which a tree falls in the forest where no one is around and one is asked, “does it make a noise?” or “does a rainbow exist

if no one is around to see it?”. The Berkeleyan answer is alluded to in the following

poem:

There was a young man who

said

“God, I find it extremely odd

that a tree as a tree simply ceases to be

when no one is around in the quad.”

“Young man your astonishment’s

odd.

I am always in the quad.

So the tree as a tree never ceases to be

Since observed by yours faithfully – God”

|